On a slippery slope behind a man with a swinging machete, I make my way through a thick bamboo forest. Thrilled that I’ve remembered to don cheap gardening gloves, I grab Jack-and-the-Beanstalk-tall tree trunks to hoist myself over rocks and up sheers of oozing mud. When I falter, a porter readjusts me, ensuring I don’t slide into the morass. A mist enshrouds our procession. As we climb, the only sound besides staggered breathing and the rhythmic chop of the ranger’s blade is the sucking plunk as boots free themselves from the muck. I’ve been told that this hike to track the endangered mountain gorillas at Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda’s Virunga Mountains could last all day. With a lunch in tote, a camera slung from my neck, and unparalleled enthusiasm, I am prepared for whatever it takes to hold court with a Silverback gorilla and his entourage. It’s a moment I’ve been waiting for my entire life.

Suddenly, we round a bend, our narrow path shadowed by so much verdant forest. The air smells suspiciously gamey and an otherworldly — yet, oddly familiar — grunting sound stops us in our tracks. A gorilla nearly six feet tall and seemingly the size of a Volkswagen blocks our way. As the first one of our small group in line behind the guide, I look right into the huge ape’s limpid coffee-colored eyes. I can’t help but think of my German Shepherd — there’s something so alert, inquisitive, and intelligent about this gaze. Behind me cameras begin to snap — but all I can manage to do is to stare, frozen with awe. The Silverback, so called for a patch of age-earned grayish hair, is the paternal leader of his family group — a coterie of more than a dozen: females, less mature males, gorilla toddlers, and infants. As if on cue, like actors appearing simultaneously on stage, the gorilla family becomes instantly visible in every direction — even from above us, where a youngster scrambles oafishly across the treetops and another swings playfully on a vine.

Our guide motions for us to move closer. He hacks a cove into the forest and we huddle there, jockeying for the best view. We’ve been told before the hike to stay at least 20 feet from the glorious gorilla clan, but there’s no place to go. Our outpost is constricted by bamboo, an entanglement of flowering undergrowth, palm-like leaves and hummocky landscape. The gorillas gather just ten feet from our throng. Like Buddhist monks in meditation, they sit very still and contemplate us. Cameras aloft, we do the same. At once, they begin to go about their business: babies suckle, adults strip bark from trees, then chew and digest it, and the young apes gambol and clamber up trees. Some attentively groom each other, a few roll about on their backs, and a pair of twins wrestle. Entranced, a friend and I move slowly from our pack. Just then, a blustering teen notices us. He beats his chest, stands on two feet, and charges our direction. As we back into the wall of trees behind us, he hunkers down to knuckle-run, moving sideways, then thumping the ground defiantly with finality just a few feet from where we stand. Our guide grunts at the incoming ape, and the ornery fellow backs down. Terrified, fascinated, and relieved, my friend and I burst into nervous giggling. “Why did he do that?” we inquire. “He’s a teenager,” answers the ranger. “He’s just like your sons — he’s showing off for you.” Great.

When famed primatologist Dian Fossey sought to get close to the endangered mountain gorillas in Rwanda, she learned to belch like them, which also has a teenage boy ring to it. In an article for the January 1970 issue of National Geographic, she described other “methods not always dignified” such as “thumping one’s chest rhythmically or sitting about pretending to munch a stalk of wild celery as though it were the most delectable morsel in the world” as the threshold she crossed to gain acceptance to these gargantuan apes. She championed them for many years in the wild, writing that “the more you learn about the dignity of the gorilla, the more you want to avoid people.” As their advocate, Fossey brought awareness to their diminishing numbers, protected them from poachers, and recorded their activities. Her lifelong studies enlightened scientists and spellbound the world. Standing more than 6 feet tall, with arm spans of up to 8 feet, and weighing nearly 500 pounds, the mountain gorillas today have a population of less than a thousand — even fewer than when Fossey gained their trust and counted them amongst her most important companions.

Now protected in various parks, including Volcanoes National Park in northern Rwanda, the gorillas live in constant motion as they forage for food. Less territorial than social, they live in loyal family groups. Fathers will raise children if a mother dies; and both parents will fight to the death to save their offspring. Gentle giants, they’re rarely aggressive. They fear lizards, caterpillars and water. Diurnal, they begin their days at dawn, ending by dusk when they create cozy nests for sleeping. With a permit, visitors can enter the park to trek with rangers and view the gorilla families, who move deftly across the borders of Rwanda to Uganda and the Republic of Congo — and back again. Only around 80 tourists a day can ascend the inclines of the park, and groups are limited to 8 people in size. The treks start early, with approved visitors entering the park around 7 a.m. There, rangers size up the fitness level of participants, then place them into groups. After a briefing, hikes into the mountains begin, with each pack assigned to one of the ten habituated gorilla families known to roam in Volcanoes National Park. Scouts ascertain the approximate location of the gorillas each morning. This knowledge allows rangers to offer shorter or longer hikes to visitors, though the length and difficulty can never be guaranteed. Once the parade of humans encounter the gorillas, they can stay up to one hour to observe them.

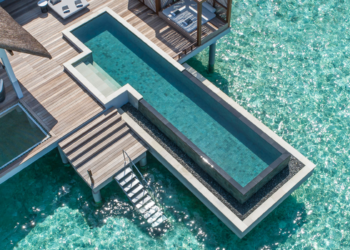

I recommend visiting the gorillas under the leadership of a tenured safari group. Volcanoes Safaris, with its luxury eco-lodge, Virunga, located atop a hill near the park, was the first luxury safari company to take tourists to see the gorillas after Rwanda became safe again for tourism after a decade of conflict. With views of two lakes and a trio of volcanoes, the lodge has eight individual bandas (stone villas with porches and mosquito-netted beds). After-trek activities include massages, hikes to the volcanoes, entertainment by local dancers, a visit to Dian Fossey’s grave, tours of village schools, and relaxation around the big fireplace in the main house. Sustainable, the property utilizes solar power, low flush toilets, and organic gardens.

Called the Land of a Thousand Hills, Rwanda also holds one-third of Africa’s bird species. An emerald garden with a friendly, colorful populace, it draws visitors for myriad reasons. But, I’ll be back for the gorillas. To see the depth and humanity in their eyes is to gaze at our past and to ponder our future. To protect them is to take care of ourselves. As Dian Fossey said: “When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate on the preservation of the future.”

Worth Booking:

Volcanoes Safaris: The safari company offers 4, 6, 7, and 10-day safaris in Rwanda and Uganda

Don’t Miss:

The Kigali Genocide Memorial Center, perhaps the best museum of its kind in the world. Scholarly, yet accessible, the museum takes a heartbreaking look at the story of Rwanda’s tragic 100 days, as well as the history of genocide in the world. Located two hours from Virunga Lodge.